Meatpaper

two

Till Dinner Do Us Part

Cannibalism strains a marriage

by Camella Bontaites and Jeremy Cantor

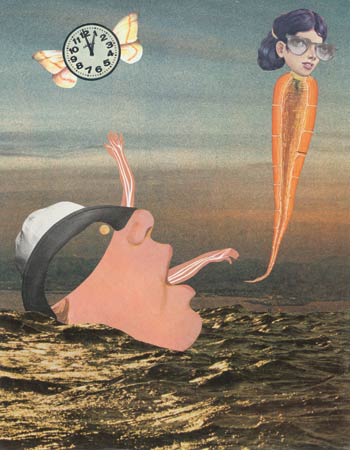

illustration

by Cy de Groat

DECEMBER, 2007

Dear Camie: Dear Camie:

Love Me Tender

by Jeremy Cantor

IT ALL STARTED a few years back when Camie and I both read

Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea: The

Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex. In the early 1800s, the

Essex was rammed and wrecked by a sperm whale and the crew

was forced into lifeboats. As supplies diminished, they turned

to the “custom of

the sea,” in which straws are drawn and the loser murdered

and consumed. One of the unlucky souls was Owen Coffin, the

nephew that the captain, George Pollard, had sworn to protect

at all costs. Philbrick writes that Pollard, asked if he knew

a man named Owen Coffin, replied: “Know him? Why, I et him!”

The question had to be asked: “What would

you do if we were stuck at sea without food?” Foolishly,

I treated it as a thought exercise instead of a test of fidelity.

I don’t

recall my exact response, but I’m guessing it began with, “I

suppose it depends...” And where did it ignite? Well,

I told Camie, if I had to eat her, I probably would.

Well, I told Camie, if I had to eat

her, I probably would.

Among

coupled peoples, amid the tolerated shortcomings and conflicts

of legitimate magnitude, a prosaic concept or two repeatedly

emerges to strike at some core value or fear, laying naked

the reality that we are separate and only somewhat controllable.

I’m talking about ostensible trivialities such as “Why

can’t you stop biting your fingernails in public?” or “How

can you really prefer cats (selfish) to dogs (loyal)?” Our

albatross is cannibalism.

Let’s be clear, eating a fellow

human deserves its spot at the top of the immorality chart,

alongside pedophilia, denying global warming, and theft from

the elderly. But undergraduate philosophy posits that morality

may be relative and established among peers, and so perhaps

a consensual cannibalistic process in the shadow of death is

not equivalent to sociopathy.

Consider the raft. Drifting toward

oblivion, there would be some compelling reasons to forgo cannibalism

and die together: romance, guilt, karmic dread, guilt, fear

of a ship coming over the horizon during the first bite, disgust,

more guilt.

But isn’t there worth in preserving life,

and in sacrifice? Take out the culinary details, and Owen Coffin’s

submission to fate looks heroic. Throw Romeo and Juliet and

their sophomoric suicide pact in my face, and I’ll toss

back my man Leo in “Titanic.” There wouldn’t

have been a movie if he’d pulled Kate off of her serving

tray to perish with him in the deep. We righteously celebrate

selfless grenade smotherers and savers of Private Ryan. Why

not celebrate the survivor, too? Is there not dignity in clinging

doggedly to life, and carrying a memory forward with grace?

Jesus remarked, “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my

blood remains in me, and I in him.” Maybe he didn’t

mean it quite so literally, but I like the sentiment. The story

should begin not that I would be willing to eat Camie if she

drew the short straw, but that, if the tables were turned,

I’d insist she eat me. In fact, I would insist on being

the one to go prior to the draw. That’s probably the

part of all of this I feel most certain about. It would be

profligate tragedy for us both to die; theoretically, someone

really should eat someone.

When we peel away the layers, what

is left is a cry, “Could

you think of me as food?” The line between coexistence

and consumption is central to what fascinates us about the

Donner Party, as are the limits of our will to survive. These

are why cannibalism parties, in which a human figure is made

out of food, are huge in Japan. Truly, I find it near impossible

to imagine eating Camie, or to imagine being eaten by her,

for that matter. It’s nearly the same as choosing to

eat you, dear reader, or our beloved cat. Small children recoil

when realizing that “chicken is chicken” but then

become accustomed. Is a hamburger more easily defended than

cannibalism for survival?

Given the remote likelihood of having

to act on the answer, it might be better to feign recoil at

the question, and avoid long trips on small boats.

Dear Jeremy: A Response to a

Husband’s

Admission That He Would, in the Event of Near-Starvation

at Sea, Take Part in Eating His Wife* If She Drew the Short

Straw.

*me

by Camella Bontaites

IT WAS THE KIND OF QUESTION I would inevitably ask after we’d

read the book. “You would never eat me, would you?” Jeremy’s

response was lightening-quick, practical. “Well, I’d

offer myself up first, but you would never eat me! We’d

have to eat someone or we’d all die... silly not to.”

A summary of the ensuing days: Eighteen queries from me — “Would

you eat Jonathan (dear friend)? Annie (childhood dog)? Your

mom?” — nine dinner-party debates, five spiteful,

muttered, cannibal references in bed as he drifted off to sleep

and one instance when I laughed sincerely and capitulated,

admiring his pragmatism.

Seeking some explanation for why a

man would eat a perfectly good wife, I scoured the Web for

anything I could find on cannibalism. I added new terms: “human

psyche,” “immortality,” “being

eaten.” I browsed our bookshelves for insights. Among

the stories we have written to ourselves throughout the ages,

I found that eating and being eaten are often linked to something

we all crave in one form or another: Control.

Humans do a powerful

thing when we eat. We make something that was here disappear,

even make it part of us. The gods have known about this trick

for ages. Chronos, the ancient Greek god of Time, ate his children.

He had lost control of them and feared them, so he devoured

them and there they stayed, imprisoned in his giant belly,

until someone gave him a vomit-inducing cocktail and they were

freed. He came from good stock, being the son of Earth and

the heavens, the grandson of Chaos and Love, but Time had little

self-control.

In the ancient Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita,

the epic hero Arjuna sees the god Krishna and cries out:

Rushing

through your fangs... men are dangling / from heads / crushed

/ between your teeth... Homage to you. Best of Gods!

Gruesome, and effective. I moved

on to the kids’ section.

As it turns out, there is plenty of cannibalism for children.

The Aarne-Thompson list of “tale types” is a hundred-year-old

repository for common fairy tale plots. In “AT 327A,

Hansel and Gretel,” the tale type of our favorite cannibalism

story, adults inveigle children to enter dark homes, forests,

and cauldrons, and threaten to control them by eating them.

Even more insidious, by nestling morals into lullabies, we

preserve ourselves and our values in our children, maintaining

a small, desperate, clawing hold on the world, even after we’ve

gone.

Meanwhile, medical anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes

writes about what she calls the “New Cannibalism” — our

need for each others’ organs and parts. In a world where

transplant surgery is a business and our bodies are our commodities,

we have become, quite literally, desperate for each other.

We consume each others’ parts to control the amount of

time we have here. But our need will never be satisfied, because

underneath it all lies an impossible task: staving off death.

Maybe that’s all Jeremy wants: more control, more time.

I could try to relent, relax about him handing me over to a

boatful of salivating sailors. Hmm. Yesterday, I wrote him

a tale, strung together from the Aarne-Thompson list:

AT, The

girl and the troll. AT 1468, Marrying a stranger. AT 9, The

unjust partner. AT, The man who wanted to get rid of his wife.

AT 1450, Clever Elsie. AT 890, A pound of flesh. AT 425a, The

search for the lost husband.

Control is an illusion. Nothing

can tell us how to transition from warm beds to a cold world

each morning with confidence, to look ourselves in the eye

and say, I am supposed to be here, everything will be OK. There

is no panacea for existential terror, no amount of eating.

Just believing. And being as kind to each other as we can.

I’ll finish telling Jeremy the new tale. I’ll hug

him then, and I might just mean it.

This article originally appeared in

Meatpaper Issue Two.

|