| |

Meatpaper five

Dining for the Brave

Italian

Futurists take to the kitchen. Hide the animals and the power

tools.

by Laurie Loftus

illustrations by Cy de Groat

SEPTEMBER, 2008

SEARCHING

HIGH AND LOW in my kitchen, trying to come up with

dinner, I found some beef tenderloin, an old 70-watt light

bulb, some shaved ice, and my flute. This presented me with

a quandary, as the recipe I was considering called for a

trumpet. I’m a fairly

confident cook, and I’ve been known to tinker with a

recipe or two, so I considered some substitutions. Other valved

brass instruments — a cornet, say, or a flügelhorn — I

would substitute for the trumpet without pause. I might even

consider judicious use of the bugle. But in the end, I decided

that crossing over from brass to woodwinds was too risky, and

resolved to try the dish called “Raw Meat Torn from Trumpet

Blasts” the next time my marching band friends stopped

by. SEARCHING

HIGH AND LOW in my kitchen, trying to come up with

dinner, I found some beef tenderloin, an old 70-watt light

bulb, some shaved ice, and my flute. This presented me with

a quandary, as the recipe I was considering called for a

trumpet. I’m a fairly

confident cook, and I’ve been known to tinker with a

recipe or two, so I considered some substitutions. Other valved

brass instruments — a cornet, say, or a flügelhorn — I

would substitute for the trumpet without pause. I might even

consider judicious use of the bugle. But in the end, I decided

that crossing over from brass to woodwinds was too risky, and

resolved to try the dish called “Raw Meat Torn from Trumpet

Blasts” the next time my marching band friends stopped

by.

All this thinking was making my stomach

growl, so I returned to my source for more options. Flipping

through The Futurist Cookbook, I began to suspect I was getting

no closer to dinner. In the trumpet recipe, for example,

the instructions were clear enough, but was I truly meant

to pass an electric current through my beef, marinate it

in a mixture of rum, cognac, and white vermouth, and serve

it on a bed of red pepper, black pepper, and snow? And, apart

from my difficulties in the kitchen, what of the challenges

awaiting me once I finally sat down to eat? In the spirit

of audience participation (or reader-as-author, or whatever

you call your favorite postmodern interpretive trip), my

meal would be complete only when consumed as directed: “Each

mouthful is to be chewed carefully for one minute, and each

mouthful is divided from the next by vehement blasts on the

trumpet blown by the eater himself.”

Enter meat. Electrified meat. Meat

imbued with perfume. Meat infused with steel.

Call me faint of

heart, but I shuddered to think of the collateral damage in

the wake of these staccato toots of pre-chewed carpaccio.

Upon

further inspection, this “cookbook” offered

few options that seemed more palatable, or practical, even

for more festive occasions. As enthusiastic as some of my friends

are about their meat, I wondered how they might react when

presented with “The Excited Pig:” “A whole

salami, skinned, is served upright on a dish containing some

very hot black coffee mixed with a good deal of eau de Cologne.”

Maybe

it was foolhardy of me to seek my next meal in a book with

Manifesto in its title.

The Manifesto of Futurist Cookery (The

Futurist Cookbook) was published in 1932 by Filippo Tommaso

Marinetti, Italian Futurism’s

founding father and front man, as a gastronomic coda to a cultural

movement that had, for largely political reasons, surged and

receded over the previous few decades. Marinetti and some like-minded

young painters and poets made their mark with the original

1909 Futurist Manifesto, a bombastic screed against nothing

less than 400 years of Italian history and its entire cultural

and social infrastructure — schools, churches, museums,

the lot.

The 1909 manifesto would form the template,

in spirit (“Don’t

trust anyone over 30”) if not in substance, of just about

every avant-garde/punk movement to follow. Take a bilious contempt

for middle class conventions and sensibilities, add a little

leftist populism for good measure, and bind it all with a love

of machines, militarism, and masculinity. “We declare

that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty:

the beauty of speed. ... We want to sing the man at the wheel.

... A roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire

is more beautiful than the Victory of the Samothrace.” Their

aesthetic will be familiar to fans of French Symbolism, Godard,

Brecht, and Johnny Rotten: “The essential elements of

our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt. ... Poetry

must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown. ...

Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that

has not an aggressive character.”

Despite their Clockwork

Orange rhetorical posturing, Marinetti and his droogies seemed

to be motivated by a heartfelt desire to pull their beloved

country from what they saw as the quicksand-like suck of its

classical past. Since this is Italy, it should come as no surprise

that such an appeal to the “sympathizers

of the New Italy” would reach into the country’s

most profound expression of national identity: food culture.

Their first order of business in The

Manifesto of Futurist Cookery: Go for Italy’s jugular.

Get its people to put down their pasta.

In a diatribe that

would thrill today’s anti-carbohydrate

fundamentalists, the Futurists launched an all-out assault

on the mangimaccheroni. While it is deemed “patriotically

acceptable” to substitute other starches, such as rice,

pasta is proscribed. Pasta eaters, they claimed, “forget

the lofty dynamic obligations of the race and the searing speed

and most violent contradictory forces that constitute the agonizing

rush of modern life.” In a delightful and peculiarly

Italian moment, Marinetti has to admit that pasta is delicious,

but he calls on progressive Italians to resist the lotus-like

lure of pasta, “a passéist food because it makes

people heavy, brutish … skeptical, slow, pessimistic.”

Pasta

represents individual regression and collective de-evolution:

Eating it demonstrates a failure to exert impulse control.

It is “a piggish enjoyment,” “short-lived

bliss,” “a debased and suburban form of pleasure.” Just

as the soothing pastoral scenes of realist painting are seen

to encourage a passive contemplation of life’s surface

pleasures, pasta eating is viewed by the Futurists as an anodyne

for middle-class malaise, the pasta eater attempting to fill

the gaping “black hole” of modern existential angst

and melancholy. “He may delude himself, but nothing can

fill it. Only a Futurist meal can lift his spirits.” To

marry a catch phrase from Italy’s favorite Marxist son,

Antonio Gramsci, with the Futurist cookbook banner: Pessimism

of the intellect, optimism at the table.

Enter meat. Electrified

meat. Meat imbued with perfume. Meat infused with steel. Animals

served inside, beside, and on top of other animals. And (with

apologies to the Sex Pistols) never mind the Venus de Milo,

here’s the Sculpted Meat: Enter meat. Electrified

meat. Meat imbued with perfume. Meat infused with steel. Animals

served inside, beside, and on top of other animals. And (with

apologies to the Sex Pistols) never mind the Venus de Milo,

here’s the Sculpted Meat:

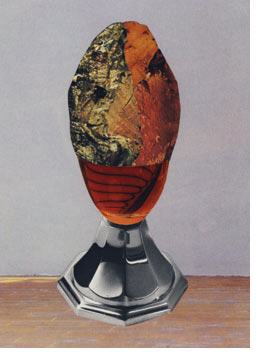

“Sculpted Meat” (a synthetic

interpretation of the orchards, gardens, and pastures of

Italy) is composed of a large cylindrical rissole of minced

veal stuffed with eleven different kinds of cooked vegetables.

This cylinder, standing upright in the middle of the plate,

is crowned by a layer of honey and supported at the base

by a ring of sausages resting on three golden spheres of

chicken meat. A marvel of balance.

If pasta is anti-virile,

meat represents the ability to grab modern life by the coglioni.

For the Futurists, the body is the machine of industry; its

engine, the brain. Its liveliness and energy are essential

to progress. “The great consumers

of pasta have slow and pacific characters, while meat eaters

are quick and aggressive.”

“The stomach,” says Marinetti, “expands

at the expense of the brain.” To eat meat is to ingest

energy in its most immediate form. Meat stokes the fire that

forges the new national identity. Meat increases individual

virility, which leads to national superiority. Meat confers

power. Power is sexy. Transitively, with all due apologies

to vegetarians: Meat is molto sexy.

But Futurist meat is

hardly caveman fare; meat is a food to be manipulated as

an artistic material, in a kitchen far from the homey hearth

of nonna and closer to the mad scientist’s

laboratory or the metalsmith’s foundry. “We speak

very precisely of the need to make use of electricity and of

all the machines that can improve the work of cooks.” Concocting

meals of meats surrounded by foams, vapors, oils, and smoke,

the Futurists predict and predate the wit, whimsy, and sensory

acumen of molecular gastronomists by 50 years. They bring the

sights, sounds, and smells of the city onto the plate, as if

the animals had been pulled, dusted in soot from urban streets

choked with Fiat exhaust and factory fumes. As if this were

a good thing.

For all their avowed interest in powering

the modern Italian body, the Futurist diet seems richer in

irony than iron. The symbolic value of their (literally)

tongue-in-cheek meat dishes could, I suppose, be understood

as an ongoing commentary on the dominance of technology over

nature, but it also mocks such an earnest academic interpretation,

as well as the dogma surrounding Italians’ cooking

and eating. For all their bombast and grandiloquence, what

the Futurists really seem to champion is a kind of culinary

absurdity that finds its counterpoint in a more kitchen-worthy

Italian classic, The Silver Spoon, the 1,200-page tome widely

regarded as “Italy’s

Joy of Cooking,” whose frontispiece declares, in bold

type:

EATING IS A

SERIOUS MATTER

To the Futurists, cooking is an expression

of imagination as high as in any art form. Likewise, to eat

is to contemplate a three-dimensional artwork “whose

original harmony of form and colour feeds the eyes and

excites the imagination before it tempts the lips.” Calling

for some of their dishes to be served with swatches of

velvet, sandpaper, and silk, they do take the experience

of “pre-labial sensations” rather

seriously, but they advocate improvisation and play on the

traditional modalities.

With that in mind, I sipped the cocktail

I’d mixed while

browsing the cookbook and glanced around my kitchen again.

My eyes seized on that tenderloin and my flute. Clearly, my

old flute didn’t have the windpower to propel even the

tenderest of tenderloin into carpaccio. But if I could get

my hands on some pig intestines. ... Maybe it’s the cocktail

talking, but I’m thinking ... Fauré’s Pavane sausages with a side of raw silk?

ULTRAVIRILE ULTRAVIRILE

On a rectangular plate put some thin slices of calf’s

tongue, boiled and cut lengthwise. On top of these arrange

lengthwise along the axis of the plate two parallel rows of

spit-roasted prawns. Between these two rows place the body

of a lobster, previously boned and shelled, covered in green

zabaglione. At the tail of the lobster place three halves of

hard-boiled egg, cut lengthwise, so that the yellow rests on

the slices of tongue. The front part, however, is crowned with

six cockscombs laid out like sections of a circle, while completing

the garnish are two rows of little cylinders composed of a

little wheel of lemon, slices of grape and a slice of truffle

sprinkled with lobster coral.

VEAL FUSELAGE

Slices of veal attached to a fuselage composed of cooked chestnuts,

little onions and sausages. All sprinkled with powdered chocolate.

SIMULTANEITY

A cocktail (polibibita) of wine, vermouth and aquavit garnished

with fresh dates, stuffed with mascarpone and wrapped in

prosciutto and lettuce leaves. If the toothpick is put into

the glass, eyes of fat deposited by the ham will appear on

the surface of the liquid: In this case, the polibibita can

be called “This little piggy who makes eyes at you.”

Laurie

Loftus is a Bay Area-based fundraising consultant, freelance

copy editor and writer, aspiring silversmith, and recovering

academic (one day at a time). She will admit to playing her

flute badly on occasion, though she promises never to try

sausage extrusion for real.

This article originally appeared in

Meatpaper Issue Five.

|

|